05, 2017

In terms of sales, what are the three most important things to know about psychology? #Q&A

Question:

You can only choose three.

I have read a lot about how psychology is important for sales, but never read much about how it is used for sales. Can those more knowledgeable share?

Answer:

Here are my three:

- Bounded Rationality

- Risk Aversion | Loss Aversion

- Anchoring

________________

- Bounded Rationality – Articulated by Herbert Simon (Nobel Prize Winner for Economics, 1978).

Organizations do not make optimal decisions because they operate under the condition of imperfect information and individual biases. Simon referred to this as “satisficing.” (“Rational Choice and the Structure of the Environment,” Herbert Simon, 1958. Link: http://www.uta.edu/faculty/richa… )

If you’ve sold a good or service and thought – “How could they decide on company’s XYZ’s product? Ours is better, faster, and cheaper…” – this is Bounded Rationality in action. Team managers attempting to reach consensus on a project, you know the decision process is fraught with pandering, or at a minimum, accounting for individual egos and incentives. (“We can do that, but how is John going to feel about it? Maybe instead we can go with Plan B. It’s not as good but it will get the job done and appeases John.”) This is Bounded Rationality.

Anyone working in an organization of any size has witnessed this concept in action; it is particularly evident as organizations grow larger. In an organization, as individuals’ motivations and information access is limited (a.k.a. “imperfect information”), suboptimal decisions result. (This also explains why Congress passes suboptimal laws with “pork barrel expenditures”…)

In his paper “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice (1955)”, Simon articulated the difference between “economic man,” who theoretically decides rationally and optimally, and “administrative man” where the organization (“organism”) suffers from imperfect information and individual biases. (Link: http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/use…)

“The apparent paradox to be faced is that the economic theory of the firm and the theory of administration attempt to deal with human behavior in situations in which that behavior is at least “intendedly” rational,; while, at the same time, it can be shown that if we assume the globals kinds of rationality of the classical theory the problems of internal structure of the firm or other organization largely disappear. The paradox vanishes, and the outlines of theory begin to emerge when we substitute for “economic man” or “administrative man” a choosing organism of limited knowledge and ability. This organism’s simplifications of the real world for purposes of choice introduce discrepancies between the simplified model and the reality; and these discrepancies, in turn, serve to explain many of the phenomena of organizational behavior.” [emphasis mine]

In his 1978 Nobel Prize lecture, “Rational Decision-making in Business Organizations.” Page on 237.143.81) Simon refers to the individuals’ motivations as “subordinate goals”:

“In organization theory it is usually referred to as subgoal identification. When the goals of an organization cannot be connected operationally with actions (when the production function can’t be formulated in concrete terms), then decisions will be judged against subordinate goals that can be so connected. There is no unique determination of these subordinate goals. Their formulation will depend on the knowledge, experience, and organizational environment of the decision maker. In the face of this ambiguity, the formulation can also be influenced in subtle, and not so subtle, ways by his self-interest and power drives… Given a particular environment of stimuli, and a particular background of previous knowledge, how will a person organize this complex mass of information into a problem formulation that will facilitate his solution efforts?” [emphasis mine]

Have a Sales Question?

Grab a time to chat with Scott here.

Aiden Ward and Richard Veryard posted their presentation “Rationality and Decision-Making” to Slideshare. It’s a good primer for more about decision theory in organizations.

- Risk Averson & Loss Aversion

These are two related concepts in economics and psychology.

Risk Aversion: Individuals and organizations can be risk averse, risk neutral, or risk loving. In most cases, individuals and organizations are risk averse, referring to the natural tendency to avoid risky situations and bets in most cases. (This is why people buy insurance.)

As an salesperson, risk aversion can be overcome by identifying relative risk profiles of the decision team members in the target organization and developing a strategy map to adjust the positioning of your product and its affect to each individual. (Remember “Bounded Rationality” above – individuals within an organization have independent motivations and access to information.)

Mathematically, risk aversion is illustrated with a concave utility function:

The greater the risk’s payout, the less utility is realized by the individual or organization. While the potential outcome could be greater by taking more risk, the experienced gain (“utility”) decreases as the outcome gain increases. In business, this explains why organizations rarely go for the “home run” outcome unless in a distressed state where the downside risk is already mitigated by a deficient current state.

As a manager, risk aversion can be overcome by selection risk-loving team members and providing the proper incentives to the team. There is a body of academic and business literature on strategies for overcoming organizational risk aversion.

Loss Aversion: Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky developed this concept as part of their work on “Prospect Theory.” Loss aversion is an individual’s preference to avoid a loss rather than make a gain. (Kahneman won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002 despite never taking an Economics class. Tversky would likely have joined him but the Nobel committee does not award posthumously.) Under loss aversion, individuals tend to act irrationally by taking larger gambles to avoid loss than they do to realize gains. When businesses make decisions based on this premise, it means that status quo becomes more acceptable and change is only instigated when there is critical business issue that may result in a clear loss. Even if a product or service you are offering will “make this better,” this is not as strong of an influence as a product or service that mitigates a pending loss.

You often here of salespeople “selling fear.” This is loss aversion in action. The salesperson is identifying a potential business loss and selling a service that will prevent the loss from occurring.

- Anchoring

Kahneman & Tversky first described this concept in “Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics & Biases” (1974, Page on Caltech.edu)

Typically, “anchoring” is matched with pricing strategies. The sticker price posted to the car on the lot is an anchor. The dealer is setting an artificially high price in your mind, so that any negotiation down from that anchor price will feel like you have negotiated a good deal for yourself. The works even though both you and the car dealer know that no one pays sticker price for a car. The mere action of posting the price is what is effective.

Anchoring is also powerful in a qualitative sense. When interacting with your product for the first time, the prospect will develop an initial perception about your product and what it does. “Freemium” products suffer from the anchoring effect, as users are introduced to the product’s free version, become locked in, then are asked to pay for additional functionality. Because the user is “anchored” to the notion that the product is free, there can be backlash or low conversion rates. Consider that Evernote has a 1/34 conversion rate from free to paid – Evernote Wants To Be The Automatic, Trusted Place To Store Your Life [Interview] | TechCrunch.

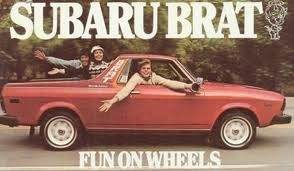

Brands are also anchored by the market, though the anchor can be overcome – Hyundai and Subaru have do so over the last 20-30 years. Think about Hyundai’s entrances to the US automobile market in the 1980’s versus their brand perception today: Hyundai�s Global Branding Strategies. Remember these cars?

Kahneman recently published “Thinking Fast and Slow” (Link: http://www.amazon.com/Thinking-F…) that describes Anchoring, Loss Aversion, and other psychological concepts for the layman.

**This Q&A article was originally posted on Quora. Check out Scott’s Quora page here.